From outputs to outcomes after the Indian Ocean Tsunami

Habitat for Humanity supported more than 25,000 families to repair or rebuild their homes following the Indian Ocean Tsunami – but what lasting effect did its housing reconstruction programme have on the families and communities it served? Last week I presented a paper at the Asia Pacific Housing Forum on lessons from Habitat for Humanity’s housing reconstruction programme after the Indian Ocean Tsunami. My presentation gave a summary of research completed by myself and my former colleagues at Arup International Development (more detailed findings are available in this paper) while proposing some key lessons for future housing reconstruction programmes after disasters.

Research question and methodology

To what extent had Habitat for Humanity’s housing reconstruction programmes contributed to the development of sustainable communities and livelihoods?

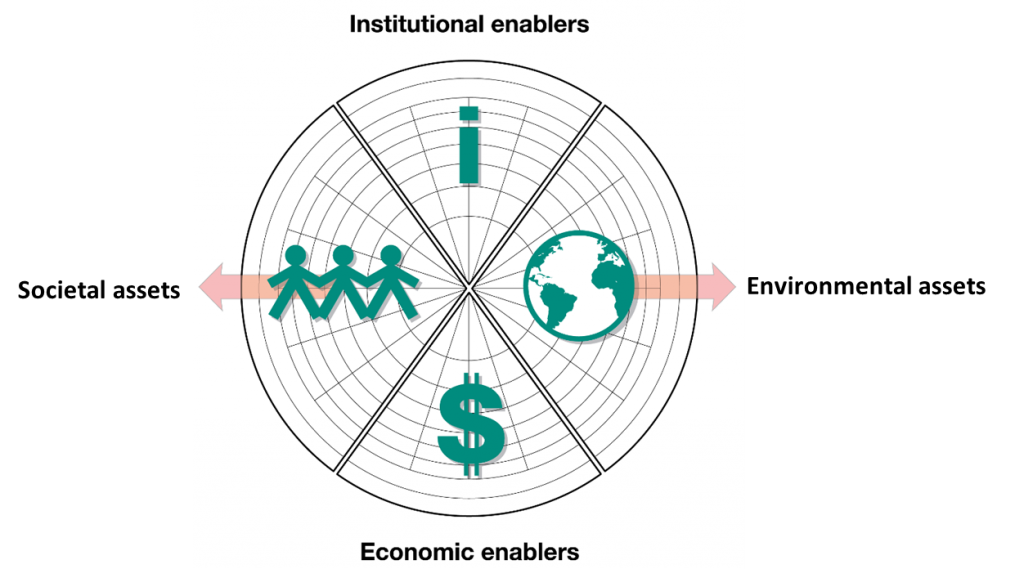

The assessment covered Habitat for Humanity’s permanent housing reconstruction programmes in Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka and India and was based on programme documentation and key informant interviews, household questionnaires and workshops with communities. Analysis was completed using the ASPIRE tool – a holistic framework for assessing the outcomes of a project or programme in terms of governance/institutions in addition to the triple bottom line of society, environment and economics. While following a common approach Habitat for Humanity’s programmes were different in each country: thus four separate assessments were completed and then compared and contrasted to draw out lessons learned.

Source: Arup and EAP (2009)

Overall the assessment found that Habitat for Humanity’s housing programme had made a significant contribution to the development of sustainable communities and livelihoods. The programme had replaced houses which had been destroyed in the tsunami, often to a higher standard and (in most cases) complete with access to services and social infrastructure. The provision of high quality core homes had reduced household vulnerability and increased the standard of living (with benefits to health and well-being) while the organisation’s participatory process had increased community cohesion. However there were a number of areas where small changes in programme design or implementation could have increased the positive outcomes of its work.

Housing as a product

The assessment found that Habitat for Humanity’s focus on rebuilding houses in-situ had had significant benefits in terms of maintaining household’s access to existing social networks, education, healthcare and livelihoods. However, improvements could be made in hazard assessment, planning and infrastructure at a settlement level in order both to reduce exposure to hazards through localised relocation or infrastructure provision and to ensure that it is not just houses which are rebuilt but communities – complete with spaces for education, healthcare, livelihoods and recreation.

The organisation had typically constructed high quality, disaster resilient ‘core homes’ – complete with access to water, sanitation and electricity at a household level – and this had reduced household vulnerability and increased the standard of living. However, many of the households visited had made similar alterations and extensions to their houses (for example converting bedrooms to prayer rooms or adding kitchens) just 2-3 years after their completion. Consequently in the paper we question whether this is a positive indicator (showing households taking ownership of their new housing) or demonstrates a significant investment of time and energy during the recovery process in order to adapt a core home which was not completely suited to their original needs.

In several instances Habitat for Humanity had also introduced new construction materials (such as concrete blocks), techniques (such as ring beams to improve seismic performance), or technologies (such as toilets or solar cookers). While these examples show the organisation striving to deliver the highest quality housing within the time and budgets available, the assessment found that the materials, techniques and technologies introduced were not always continuing to be used, and that they were easiest for households to maintain, adapt, and replicate themselves when they were incremental improvements on existing techniques.

Habitat for Humanity’s core home design (far right) in one community in Indonesia which incorporates the re-use of a timber transitional shelter as a kitchen (right) and later extensions using a combination of timber and other materials (centre and left).

Housing as a process

In general the assessment found that Habitat for Humanity’s participatory process had increased community cohesion and that the organisation’s commitment to working with partners had strengthened relationships between the communities it worked with and a range of external actors. However, in the paper we question the level of participation in Habitat for Humanity’s housing programmes with reference to Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation (see below). We ask whether the rapid alterations to the core homes provided, and challenges experienced introducing new construction materials, techniques and technologies, indicate that higher levels of participation (i.e. participation in decision-making rather than construction) are required to ensure future programmes fully meet the needs of the communities they intend to support.

What level of participation is appropriate or possible in relief, recovery and reconstruction programmes?

Source: Arnstein (1969)

Livelihoods remained a challenge for many of the communities visited but the assessment found that the more households and communities were involved during construction the greater the benefits in terms of livelihood diversification. However it also highlighted that opportunities for employment generation during construction were missed in several cases – suggesting the need for a more holistic approach to livelihood support and the potential for partnerships with other organisations with specialist expertise in this area.

Lessons to be learned

Supporting more than 25,000 families was a tremendous undertaking and this assessment, paper, and blog post cannot possibly describe the complexity of the programmes or the nuances of all the lessons which can be learned. To try and synthesise though I suggest the following four lessons – but I’d be very interested in hearing your views!

- The challenge of adopting participatory approaches to housing programmes given the speed and scale of post-disaster programming but the need for greater participation in decision-making throughout project design, construction, maintenance and replication if we are to really meet the needs of the families we hope to serve.

- The importance of considering the long-term use of houses, infrastructure, construction materials, techniques or technologies from the outset. Will families be able to maintain, adapt, extend or replicate any new interventions themselves?

- The need for greater consideration of settlements in addition to houses to reduce risk and ensure that it is not just houses which are rebuilt but communities – complete with spaces for education, healthcare, livelihoods and recreation.

- The importance of a holistic approach to recovery – considering reconstruction of housing and infrastructure as only one component and maximising the contribution of all humanitarian interventions to the social, economic, environmental, cultural and political recovery process.

It would be interesting to contrast approaches like this to slum upgrading enumerations which aim to take a whole settlement approach as you suggest in your post. How do you reconcile maintaining ‘community’ while also considering redesigning space to incorporate amenities and public spaces that might not have existed before

Hi Caroline, This is a good point. I think I’ll do another post on how different organisations tackled this problem in Indonesia after the tsunami, but I agree we also have lots to learn from developmental approaches. Thanks

Great summary of a complex set of programs! I had never thought of the “additions, expansions etc” of core homes as possible indicators of the inadequateness/weakness of the core home. This is very interesting. I wonder to what extent people expanded and “abandoned” the core home vs expansion as the natural process, facilitated by the provision of a core home? How would an organization like HfH redesign their program accounting for a certainty of future expansion?

I’ve discussed this point briefly with Victoria during the Asia-Pacific Housing Forum. Most Habitat for Humanity house designs are ‘incomplete’ which makes house improvement and extensions an ‘anticipated outcome.’ Furthermore, I see these efforts as a coping way for disaster victims. After a disaster, one of the psychological impact a family experiences is helplessness and lack of control of things. Hence, doing alterations to one’s shelter after a disaster may be their way of gaining and realizing some control in their lives. I find this an empowering experience, rather than a weakness in design.

Hi Gerry. I agree that efforts of home expansion promote recovery not only at a material level but also a psychological one. Good point!

I wonder still how this “anticipated outcome” is actually reflected in terms of design. Is it simply that a house is incomplete? Or are anticipated expansions discusses with the household, so that the core home best lends itself to promoting such expansion. In Port-au-Prince as in many other urban contexts around the world, houses usually expand up (adding additional floors). This is often problematic when it comes to seismic safety. So it would be important for people to start thinking about design in anticipation of such expansions, to ensure that these are safe…

Gerry/David – thanks for the comments! I totally agree with Gerry that making improvements to your home is part of psychological recovery. I just also think that we should be careful not to assume alterations and extensions are always a ‘good thing’. I think when we do longitudinal research it’s important to dis-aggregate between alterations because of desire and those because of need. It’s not something we looked at specifically in this study but it’s something I’d like to investigate further.

Hi Victoria, Thank you for sharing this issue, especially about the outcome after the housing reconstruction projects done. I think this is very important to know what is the impact of the housing project in the community. This report show that the project design of the housing reconstruction project is very crucial for the sustainability in the affected community. I think in the post disaster housing project, many organizations build a lot of houses with various models and concepts in the affected areas and then they are leaving without considering what is the impact of their housing project to the affected community. About what the appropriate level participation in the relief,recovery or reconstruction programes, I think the modified of The Ladder of Participation by Choguill (1996) is more visible that empowerment is the best level, and the empowerment can be seen in the outcome of the project