Post-disaster decision making

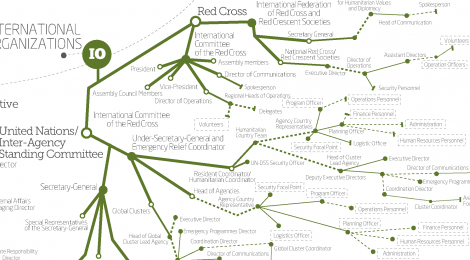

Disaster recovery can be described as a ‘process of interaction and decision-making among a variety of groups and institutions’ (Mileti, 1999). It is also complex, multi-dimensional, non-linear, uncertain and conflict-laden, with outcomes ‘strongly influenced by decision-making, and conditioned on institutional capacities’ (Chang 2010). Some researchers claim that the key difference between pre- and post-disaster conditions is time compression. From their perspective the disaster recovery process can be understood as an abnormally large demand for capital services (such as housing) and a correspondingly large ‘increase in the demand for decisions, information flows, financing, and institutional formation’ (Olshansky et al. 2012).

Source: Olshansky et al. (2012)

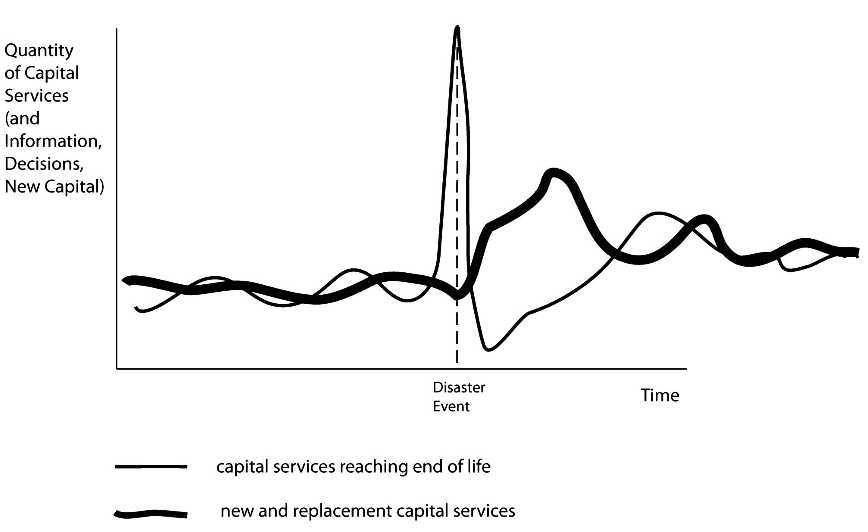

In addition to volume the complexity of decisions also increases. I’ve mentioned before the challenges of balancing short term needs and long-term aspirations but I think you could argue this is always part of decision-making. By definition in a disaster local capacity has been overwhelmed and so disaster recovery always involves both emergent and external groups and organisations. I think a critical difference between pre- and post-disaster situations is the complexity of stakeholder relationships; indeed a recent mapping of humanitarian decision-makers identified more than 130 actors in eight key stakeholder groups. What interests me is how this network of individuals, groups and organisations make decisions – individually or collectively – based on the different motivations, mandates, capacities and resources of all the different actors involved.

Source: Decision Makers Needs Community (2013)

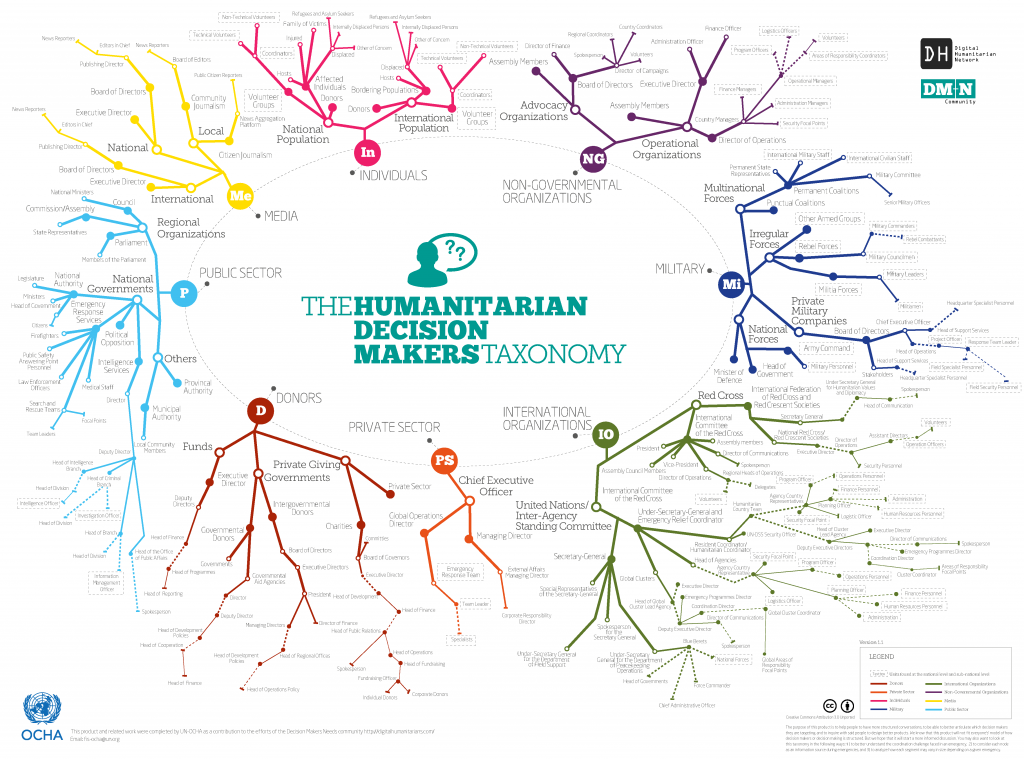

Within the humanitarian community there is currently significant interest in evidence-based decision-making but authors note that response analysis remains largely eminence-based – i.e. the domain of ‘experts’ and specialist advisors. In deciding on an appropriate response the specialist advisor plays a critical role in appropriately synthesising explicit and tacit knowledge from both situations in order to extract relevant lessons from one situation in order to apply them to another. Being only human however, these ‘experts’ are subject to individual and organisational biases, assumptions, and preferences. Many of us will recognise from experience that ‘people become specialized in something and it becomes more and more difficult to have an open mind and look at other responses options’ (Darcy et al, 2013).

Source: Borton (2002)

Disaster recovery involves decisions about large amounts of money and ‘that combination is politics’ (Olson, 2000). Government officials face not only the challenge of managing the recovery process, but also of demonstrating their compassion, correctness and credibility, while providing an adequate explanation of why the disaster occurred (Olson & Gawronski, 2010). Researchers have suggested that disasters can be categorised as accidents, emergencies, disasters or catastrophes depending on the level of organisational response required (Quarantelli, 1987). It’s important to recognise that the political stakes also increase at each of these levels – both because increasing levels of damage highlight the failures of government policy prior to the disaster and because of the increasing scale and complexity of the response required.

From a bluntly political perspective, the purpose of mitigation and preparedness is not only to ‘save lives and protect property,’ but also to control the political stakes, to keep events from crossing the thresholds to increasingly problematic political levels. ‘Accidents’ do not really overload political systems. ‘Emergencies’ might, depending on the context in which they occur and especially if they are coupled with other events tied to larger issues. ‘Disasters’ certainly do overload political systems, and ‘catastrophes’ can bring down regimes (Olson, 2000).

My preliminary research has investigated the decision-making processes of just two of these stakeholder groups but I hope you agree that this is fascinating stuff and quite far from our current discussions within the humanitarian ‘bubble’. I’ve included the questions guiding my research below and I would very much like to hear whether you think this research is valuable and your opinion on any of the topics raised.

- Which individuals, groups and organisations make decisions about shelter and settlements after disasters? What is the relationship between them?

- What kinds of decisions do they make? How? When? Where?

- Why are these decisions made? What factors influence the decision-making process?

- What effect do these decisions have on the actions of 1) affected communities or 2) assisting individuals, groups or organisations? Which decisions are most important? Why?

- How can post-disaster decision-making be improved?

Just to be totally clear the amazing diagram at the top of this post comes from the Decision Makers Needs Community of the Digital Humanitarian Network. You can read more about it and view an interactive version here http://digitalhumanitarians.com/communities/decision-makers-needs

Victoria this is really interesting, and I really look forward to learning the answers to these questions as you move forward!

I attended recently a presentation by Richard Eisner, former coordinator of disaster response for the northern region of California. One of the things that struck me was his discussion of disasters as “once in a career events.” In fact for most of the “big” decision-makers, disasters happen only once in their careers. So the process of decision making by city officials, state governors, and other political level leaders is most often based on zero previous experience. At best, these leaders rely on advisors with experience! So what I wonder is: how do we prepare leaders for making critical decisions in once-in-career crisis circumstances?

This is a cool diagram – I wonder how they made it and how you (others) will use it.

Is it size or proxmity to the centre that is in proportion to power? The only annoying things are:

– stakeholders around the ring look equally powerful (if power is by size or proximity)

– it pre-defines stakeholders according to the mandates of international organisations.

Obviously this would bug me but an AWESOME find.

That diagram is a cool, idea but does not reflect reality that well

As an example

-the Red Cross is really divided into 4 significantly different entities in a disaster response IFRC ICRC Host Societies and Partner Societies

-Faith based agencies as implements and donors are a major entity that is over looked

-In country Governments need to be divided up in two main ways, government by level -national – provincial- district – village and by department which may exist at multiple levels within each level

Also I am not sure that this in anyway represents who actually makes decisions, and that in fact the decision makers change over time.

Finally as with faith based groups I mention above, decision makers are individuals and they may and often do have multiple roles. When Yogya Earthquake destroyed my village, I was a resident, the director of a local NGO, an affected person, I worked for Oxfam and then The Red Cross and then the UN where I was embedded in government, I was a donor, a writer for the alternative press etc This multiplicity of roles is actually the norm for decision makers and has significant effects.

Let me share two anecdotes which was experienced here in the Philippines during and after super typhoon Haiyan in relation to shelter decision-making. A day before Haiyan made landfall, many communities sought refuge within larger, supposedly more stable structures of churches. But, at the height of the onslaught, one of the relatively big churches in the Visayas gave way; its roof debris falling down and killing at least two and injuring a few people taking shelter there. In another facebook post, survivors were supposedly refused shelter by a local church which remained standing, simply because they were not “members” of the church. (This story, fortunately turned out to be a hoax done in very bad taste.)

My point here is that what I find “missing” (or could not locate yet) in the diagram is the role or influence or the factor or ‘local faith groups’ in disaster decision-making. Maybe it’s not too eminent on a global or international scale, but the accounts I shared above made me think further that for some communities, ‘faith and/or religion’ does come into play when they choose to evacuate to a church rather than a government structure (usually schools or similar communal facilities like a sports/basketball covered courts.)

I think, Victoria, this was also brought out in one presentation during the AP Housing Forum, particularly the one story when people refused to evacuate because their ‘local priest’ told them the dam would keep them safe (?).